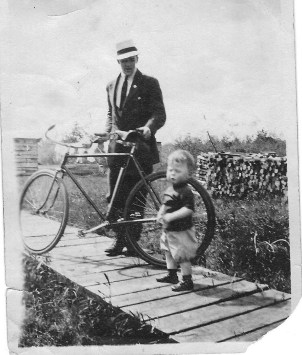

Harold at home, shortly after returning from England. Toddler is likely his sister’s son.

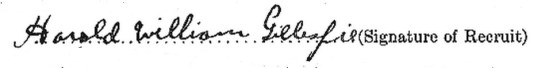

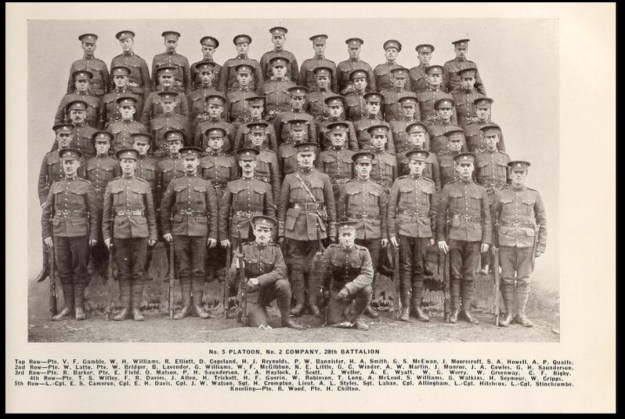

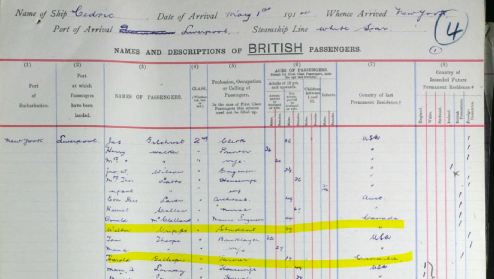

Once Harold signed his attestation papers, he became a member of the 101st Ballalion of the CEF. The National Archive has a scanned copy of the 101st Battalion’s Nominal Roll of Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers and men. I check that Harold’s name and details are there. As I scroll down the roll, I see most of the men on it were younger than 22 years old.

I find the nominal list is full of other hard facts, all organised into neat columns so it’s worth spending more than a few minutes on it, to get a clearer picture of this group of men-boys who have answered a call.

First, I do a quick estimate of the pages of names on the roll; there are over 1000 of them (CEF expert, Jim Busby later informs me there were 36 officers and 1032 men in the 101st). Next, the column labelled ‘Former Corps’ shows that less than a quarter of the recruits had experience with soldiering before enlisting. Other columns show:

- only one-third of the men were born in Canada, the majority were from England/Scotland/Ireland

- less than a quarter were farm boys from the prairie

Under the names and addresses columns I find a father and son who enlisted together; there are brothers, cousins, and boys who lived next door to each other. At this stage, it still looks like Harold travelled to Winnipeg on his own to sign up, but I wonder if anyone he knew might have enlisted into the Battalion at another place or time. I re-scan the roll, looking in the appropriate column for anyone from his hometown or from other towns and villages in the Swan Valley. I find two other names from Durban (his hometown): Albert John McRorie and Clarence George Braden. There are also a couple of boys from the neighbouring town of Kenville: Andrew John Davis and George Irwin Greig.

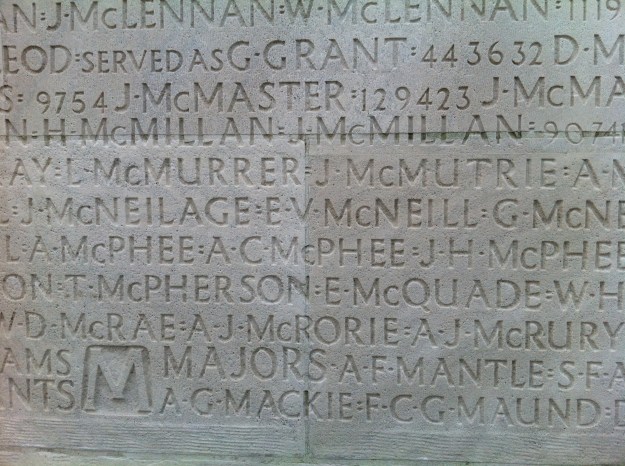

Albert John McRorie

According to local history books, the McRorie’s and the Gillespie’s were among the first families to settle in the Durban area and when I check the 1906 census, they are just a few families apart on the page so must have lived nearby. Albert is listed as ‘Bertie’ on the census and is a year younger than Harold. His attestation papers show he travelled down to Winnipeg too and enlisted a little over five weeks after Harold.

Bertie and Harold didn’t remain in the same battalion once they arrived in England. Harold was assigned to the 17th Reserve Battalion then to the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles. Bertie ended up in the Canadian Infantry 46th Battalion. Bertie’s battalion fought in every major battle attributed to the Canadian Corp, clocking up 1,433 killed and 3,484 wounded (a 91.5% casualty rate). It became known as the “Suicide Battalion.” Bertie became one of those casualties at Vimy Ridge on April 11th, 1917.

I looked for and located Bertie’s name on the Vimy monument when we visted in 2015

Clarence George Braden

Clarence Braden was three years younger than Harold (not quite 17) when he enlisted in Swan River around the same date as Bertie signed up Winnipeg. After training and shipping out with the 101st Battalion, Clarence was transferred to the 17th Reserve Battalion before being assigned for a short time to the 46th Battalion. He was then reassigned to the 24th Battalion (Victoria Rifles). On 27th May, 1918, he was one of four men in his battalion killed in action at Mercatel during an enemy raid of the front line on the Arras-Bapaume Road.

He is buried in the Wailly Orchard Cemetery in France.

Andrew John Davis

Andrew John Davis, from Kenville is slightly older (nearly 22 years old). He’s originally from Wales, married, his occupation was as a clerk and he’d also had previous military experience with 101st Regiment Edmonton Fusiliers (and under this fact is written ‘Canadian Ordnance Coy’). According to a medical board inquiry in his records, he’d been hit by a vehicle in the summer of 1915 while training with the Fusiliers. His injuries were severe including having a fractured skull. In 1916, after re-enlisting with the 101st Battalion, he was assigned QMS (Quarter Master Sgt) and he continued to clerk with the COC (Canadian Ordnance Company) throughout his time overseas. He rose to the rank of Staff Sargeant in the final years of the war and was demobilised in Winnipeg in July 1919.

George Irwin Greig

George Irwin Greig’s file had not been digitised (or any details made available) until very recently and the information it reveals brings a significant change to Harold’s story. George Irwin’s regimental number turns out to be 700056. The date on his attestation paper is December 3rd, the place of enlistment-Winnipeg and the medical officer’s signature matches the one on Harold’s papers exactly. It looks like Harold travelled to Winnipeg and enlisted with a mate after all!

George is a year and a half younger and like Harold has been working on the family farm. His service records show that after arriving in England he is also transferred to the 17th Reserve Battalion until late August, 1916 when George is reassigned to the 16th Battalion. In mid October, he suffers a gunshot wound (or scrapnel wound – differing reports on records) during fighting in Cambrai. The injury is severe enough that he is shipped back to England where an amputation is carried out above the elbow on his left arm and he spends the rest of the war convalescing. In February 1919, he is deemed medically unfit and sent home to Canada.

It’s surprised me how enormously helpful the nominal roll has been in building a picture of Harold at the most important threshold of his life. His name is on the paper and along with more than a thousand others, he is about to become a soldier. But he is not a person with a military background or military aspirations; he’s a farm boy from the new frontier of Canada. The nominal roll has also allowed me to leap ahead and see the future for four of the other local boys; futures that could have just as easily been Harold’s own future. And so now I have a question.

Question: How did the Canadian Expeditionary Forces manage to turn a pioneering farm boy like Harold into Private Gillespie 700033?

*****

According to Veterans Affairs Canada, Bertie was one of nearly 3,600 CEF men who died at the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Bertie and Clarence were two of 66,000 Canadians who would not return home.

George was one of the 144,606 battle casualties suffered by Canadian troops.

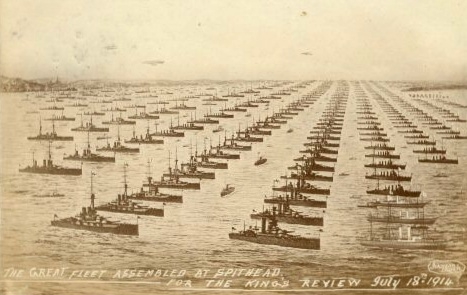

It’s important to step back and relate what’s been learned to relevant history sources and any issues that might be found in the wider context of history; things that might have affected Harold’s decision. After some reading, two issues stood out for consideration. There were news reports of

It’s important to step back and relate what’s been learned to relevant history sources and any issues that might be found in the wider context of history; things that might have affected Harold’s decision. After some reading, two issues stood out for consideration. There were news reports of

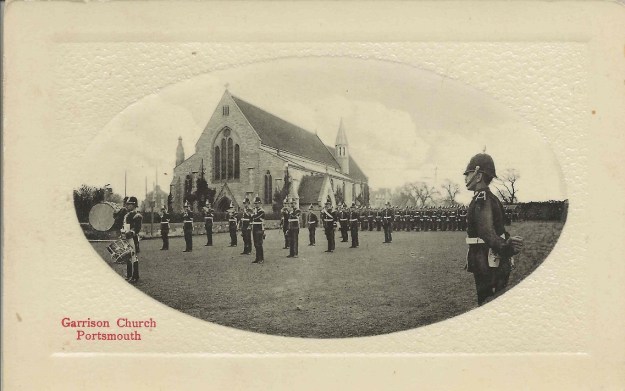

![By Rennett Stowe from USA (Royal Garrison Church) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://haroldwenttowar.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/royal_garrison_church.jpg?w=413&h=279)

!["Bellingham 1909" by Sandison, J. Wilbur (James Wilbur), 1873-1962 - Library Of Congress CALL NUMBER: PAN US GEOG - Washington no. 48 (E size) [P&P] http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pan.6a12756. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bellingham_1909.jpg#/media/File:Bellingham_1909.jpg](https://haroldwenttowar.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/bellingham_1909.jpg?w=744&h=106)